A SERMON FOR VAETCHANAN/NACHAMU – Tu Be’Av – 9 August 2025 – LIBERAL JEWISH SYNAGOGUE, LONDON

In 2014 the Knesset, the Israeli Parliament in Jerusalem, designated 30th November each year as a day with a very long title – ‘Day of the Departure for Zion and the Expulsion of Jews from Arab Lands and from Iran.’ The reason for the choice of date was because in 1947 the United Nations Partition Plan – which was to lead to Israeli Independence – was passed on November 29th. From that day onwards there were Jews across North Africa and the Middle East who found a new degree of hostility towards them, which eventually led them to leave. In many countries in the Muslim world, hundreds of years of Jewish life slowly dwindled away and vanished.

Although Jews never had full equal rights in Muslim societies, they had known for centuries how to live in peace as small but accepted minorities. Ordinary Jews were as often craft workers as they were traders. In Medieval Egypt for example, Jews were able to obtain government contracts to produce coins. Documents from the Cairo genizah record business partnerships between Jewish and Muslim weavers, goldsmiths and glass makers.[1] Maimonides was asked if it was permitted in a Jewish-Muslim business partnership for the Jewish partner to keep the whole profit from Fridays and the Muslim from Saturdays. He said Yes, that’s fine.

In Algeria, Jews became jewellers. By the 18th century – perhaps before – they were making exquisite pieces in copper, silver and gold, fine adornments for those able to afford them.

The picture above shows a traditional costume worn by a Jewish woman from the town of Tlemcen. Notice her peaked hat covered with a flowing veil, once typical in Algeria for formal attire. Notice too her necklace which is made of coins. Jews had been involved in minting coins for centuries, and it was a woman’s task to drill small holes in each one so they could be threaded onto the cord.

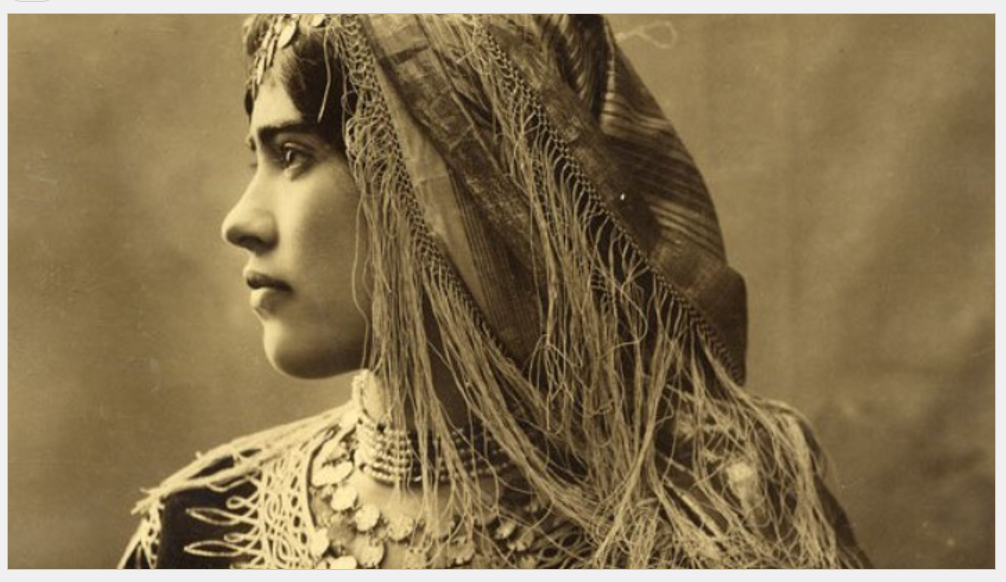

Here’s another picture (taken in 1890) of an Algerian Jewish woman, where you can see more clearly her elaborate necklaces and the coins hanging down.

Problems for Jews in Algeria were around long before today’s Middle East conflict. In the French revolution the Jews of Paris petitioned the French National Assembly to remove all the degradations they had suffered and that they be declared Citizens. Napolean regulated the professions Jews called follow and distinguished between their national and religious identity – no longer tolerated aliens but French citizens of the Mosaic faith. In 1830, Algeria became a colony of France and Jews there too were offered French citizenship. But not so many took up the offer. Many felt they were being asked to trade in their traditional way of life. In Algeria, as in France, they cleared away the little streets and the small synagogues and mosques and built large institutional ones. Crafts like jewellery were institutionalised and regulated. Gold, which had been an easily obtainable common precious metal for craft workers, was now a commodity. Not happy with the small numbers of Jews who had taken up French citizenship, in 1870 the French made it compulsory – thus dividing permanently Jews from Muslims who remained citizens of Algeria. But In World War 2, their citizenship did not help them. Under Vichy France, that citizenship was revoked and some Algerian Jews were sent to Labour camps. Their citizenship was restored after the Americans took control in 1943, helped by a group of 400 Jews. But little good did it do them as France became more and more unpopular and the French built Great Synagogue in Algiers ws ransacked by anti-Friench rioters in 1960. So two years later, when Algeria became independent from France, Jews were told by the new government that they could stay in Algeria only if they discarded their French citizenship but by that time French was their language, and most of them went to France.

This history is well documented in a new book by Ariella Aϊsha Azoulay called The jewellers of the Ummah (The Muslim world). Her parents were part of a small group of Algerian Jews – around 5% – who chose Israel rather than France. That’s where Aisha was born in 1962, and when she grew up an investigated her family history, she discovered that by the time she was born, there were no Jewish jewellers left in Algeria or in the Maghreb. No one who had practised craftwork in Algeria was able to continue in their profession in France, where Jews had never been jewellers. Thus, she said, the French murdered this ancestral tradition.

The book comes with a health warning. It is full of bitter anger both against France and against Israel, where there was no interest in those days in Jewish cultures from Arabic speaking lands. The book is a series of open letters written to friends relatives even long deceased ancestors, filled with great longing for the world that had gone, a world where Jews and Muslims lived in peace. And that’s why I’m telling you this story today on this shabbat of comfort, because when we mourn, comfort is often built on our memories. You can see her here wearing her own threaded coins, Ariella Aϊsha Azoulay, professor of modern culture and media at Brown University, in Providence, Rhode Island. Aϊsha is the Muslim name she adopted in memory of her grandmother

For centuries, millions of Jews and Muslims in many lands lived in harmony. The way Muslim culture shaped Jewish scholarship was an immense blessing. But the disruption between Judaism and Islam over the past hundred years and more has been an immense tragedy. if we are ever to have peace in the Middle East, there is a vast amount of reconciliation work to be done – not just between Jews and Palestinians, but between Ashkenazim, Mizrachim and Sephardim, between religious and secular, even between nationalists and internationalists. And those are my thoughts reading this book by a woman who calls herself ‘a Muslim Jew.’ Let us take comfort from the words of our haftarah this morning that God is the one who can bring down the hated rulers of the earth, as the people at that time had themselves witnessed. A new regime arrived and they were free.

[1] Mann, Vivian B. ‘Textiles Travel: The Role of Sephardim in the Transmission of Textile Forms and Designs’. In From Catalonia to the Caribbean: The Sephardic Orbit from Medieval to Modern Times: Essays in Honor of Jane S. Gerber, edited by Federica Francesconi, Stanley Mirvis and Brian M. Smollett, Brill, 2018, 45.